“Poverty, after all is not only among the unemployed. Most of the poverty stricken are people who are working every day.”

“Poverty, after all is not only among the unemployed. Most of the poverty stricken are people who are working every day.”

Martin Luther King, Jr., September 21, 1967

Addressing a large gathering at the International Longshoreman and Warehouse Union (ILWU) Local 10’s hall in 1967, King declared, “I don’t feel like a stranger here in the midst of the ILWU. We have been strengthened and energized by the support you have given to our struggles. […] We’ve learned from labor the meaning of power.”

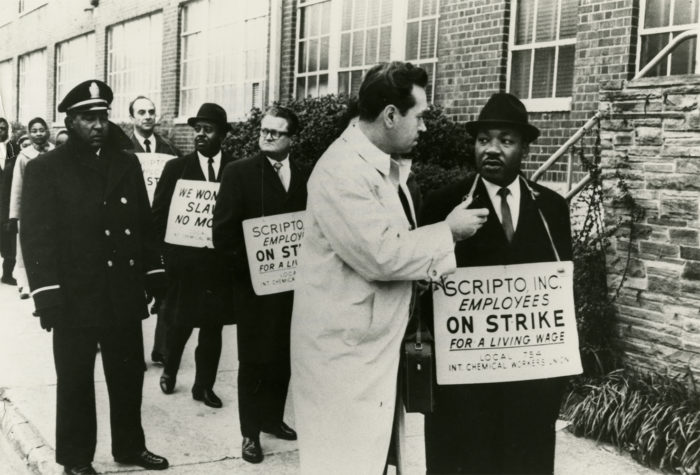

The Reverend Martin Luther King saw discrimination and anti-unionism as closely related ills. King called unions America’s first and greatest anti-poverty program. He preached about the economics of discrimination and spoke to rank-and-file members in union halls across the country. In his final years, King founded the Poor People’s Campaign.

The story of how the century’s greatest civil rights leader spoke to the ILWU that day is but one more tale in the surprising history of the labor movement.

In 1933, the longshoremen up and down the Pacific Coast set out to rebuild their union with one hard-won lesson foremost in their minds: discrimination in any form weakens a union. White San Francisco longshoreman Harry Bridges, a leader within the group, pushed racial equality because it benefited all workers. This realization connects the labor movement of last century with challenges we face today. It also connected ILWU to the Rev. King’s cause.

After strikes in 1916, 1919 and 1921, where a conspiracy of employers divided and destroyed local longshoremen unions one at a time, many unions had discriminatory policies that restricted membership to whites only. In their short-sighted bigotry, they guaranteed a group of replacements any time they tried to strike. Without solidarity, between workers in a city and amongst longshoremen up and down the coast, the unions folded.

By 1933, the Depression had made the hard life of a longshoreman much more difficult. Longshoremen would only survive if they joined unions. The longshoremen had learned their lesson. This time they were united.

The longshoremen once again applied for and obtained a charter from the ILA – but this time they established their organization as a single unit on a coastwide and industry-wide basis, thus avoiding the mistakes of the past.

Their demands were simple: a union-controlled hiring hall that would end all forms of discrimination and favoritism in hiring and equalize work opportunities; a coastwide contract, with all workers on the Pacific Coast receiving the same basic wages and working under the same protected hours and conditions; and a six-hour work day with a fair hourly wage.

The shipowners consistently refused each demand, determined to divide and destroy the unions in each port. The members of both longshore and seafaring unions voted to strike in May 1934. In response, the employers mobilized private industry, state and local governments, and police agencies to smash the unions and their picket lines.

The ranks held firm throughout the historic strike. They held up against unprovoked police violence, and withstood attempts by the ILA national leaders to cave in to employer demands for a return to business as usual. They elected new regional leaders to push the strike forward in defiance of both the employers and the ILA officials. Prominent among the new faces was a San Francisco longshoreman named Harry Bridges, who was later elected president of the ILA’s Pacific Coast District and then president of the ILWU.

In July of 1934, when it was clear the longshoremen and their seafaring allies were not going to give up their struggle for justice on the waterfront, the employers decided to open the struck piers using guns, goon squads, tear gas, and the National Guard. They provoked pitched battles in San Francisco, Portland, Seattle, and San Pedro. Hundreds of strikers – and bystanders – were arrested and injured. On July 5, known ever after as Bloody Thursday, two workers were shot and killed. A total of six workers were shot or beaten to death on the West Coast by police or company goons during the course of the strike.

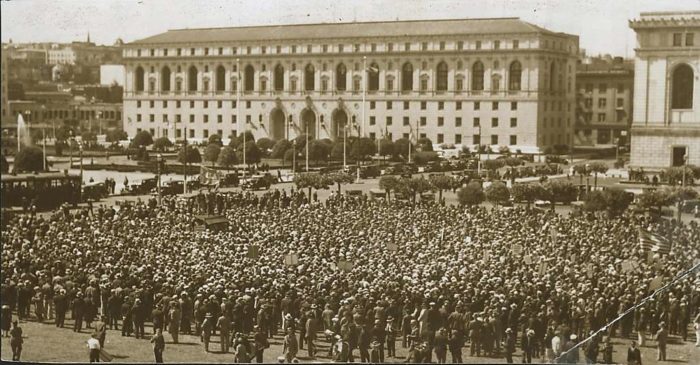

Workers in San Francisco during the 83-day 1934 Maritime strike.

Rather than breaking the strike, these terrible events galvanized public support, and prompted the unions of San Francisco to declare a brief but historic General Strike to support the longshore and maritime unions and protest strikebreaking by employers and police. The most conservative leaders of the San Francisco labor movement headed the General Strike, and called it off July 16 after just four days. Still, business and government now knew the maritime strikers had the overwhelming support of the Bay Area’s rank and file trade unionists.

Overseas support for the strikers also helped impress the employers with the impossibility of beating the strike with scab longshoremen and scab crews. And for the first time, most minority workers refused to scab, thanks to the longshoremen’s developing policy against racial discrimination. After the federal government intervened, the union agreed to arbitrate all issues – and won, in principle, each of its major demands.

By 1942, Local 10, the San Francisco branch of the International Longshoremen’s & Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU), was the sole union speaking out in internment of over 100,000 Japanese American and Japanese people to internment camps.

Why would Goldblatt and the ILWU fight on behalf of these Japanese Americans when almost no one else did? […] In the hiring halls that they built, the member who had worked the least amount of hours in that portion of the year would get the first job dispatched, the “low man out” system.

Local 10 continued to stand in solidarity with a variety of groups fighting for civil rights through the decades that followed. By 1967, when Martin Luther King came to speak to the group, the local union made Dr. King an honorary member.

When Dr. King was assassinated, the longshoremen showed they truly regarded him as one of their own.

Traditionally when someone dies on the waterfront, longshore workers stop work for the rest of the shift to honor the fallen. And, so, when word spread of King’s murder, Local 10 shut down the ports of the San Francisco Bay.

Martin Luther King’s impact on the labor movement may not be common knowledge, but it undeniable. ILWU’s tribute to King the day he was murdered is but one acknowledgement that King’s push for civil rights left an indelible mark on the labor movement.

This is the fifth in our series of posts about Martin Luther King, Jr., to mark the 50th anniversary of his assassination in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968. Read the fourth installment here.

Next, read the sixth installment, about AFSCME President Jerry Wurf’s strong and consistent support of Martin Luther King, here.